Hello players! My name’s Barry Meade from Fireproof Games, an independent games developer from Guildford, UK. Today I want to tell you about our journey from making mobile games to releasing a virtual reality game.

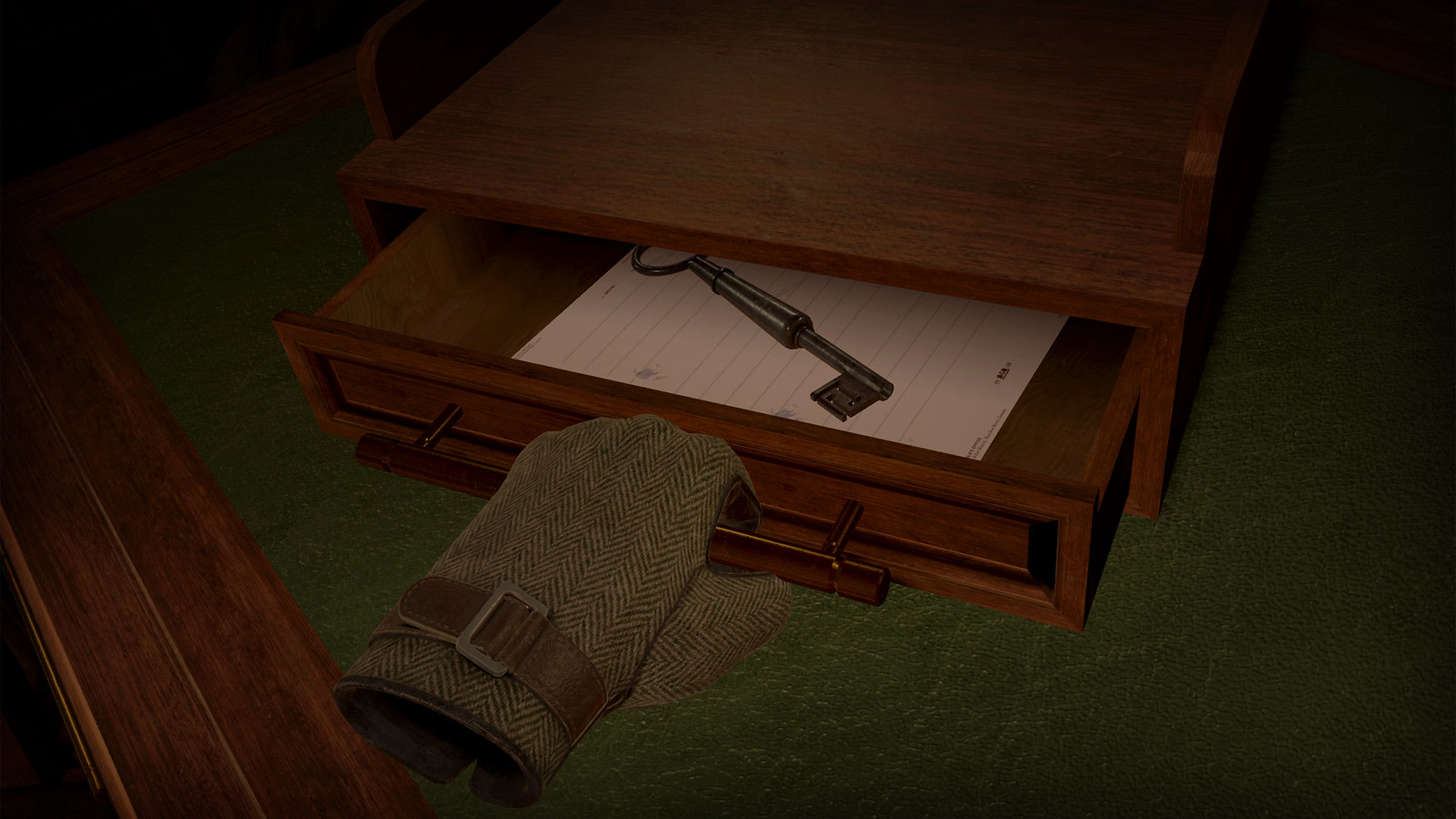

Way back in 2012 we released our first game, a small and creepy puzzler called The Room on mobile devices. At that time most mobile games used a virtual d-pad as a control method, which as console gamers we felt was lacking compared to a real controller such as a DualShock 4. So, we decided to design The Room using the touchscreen itself as a control method. The universe of The Room would exist just under the surface of the glass, where players directly pushed objects around the game world using their fingers.

We modeled the physics of every switch, lever, lock and clasp for realism so each object and piece of bizarre machinery you meet in The Room had weight and heft, adding a fun element to the snap and twirl of metal interlocking with metal as the player solved one conundrum after another. After listening to feedback, we know that our players loved the tactile feel of control this gave them.

So now you know we’ve made a game famous for manipulating 3D objects using your hands — why is this important? Well, because every day since 2012 we’ve known The Room could make a killer VR game. But only if it’s done right — as an entirely new game designed exclusively for VR, where we can take the tactile gameplay we’re famous for and properly translate it to new technology and hardware. And now, after more than 1.5 years in development, our new game, The Room VR: A Dark Matter, demonstrates that an idea we came up with for mobile devices in 2012 may find its purest expression on console VR in 2020.

So, am I here to tell you just how brilliant and perceptive Fireproof were eight years ago? Well, as much as that sounds appealing, no. In fact, I want to tell you the opposite. We thought The Room would translate perfectly to VR but sometimes what seems obvious on the surface is only that — obvious on the surface. I want to give you an insight into how our assumptions went stupidly wrong.

Here’s just four ways VR schooled our asses:

1) We should totally watch people playing the game to learn their reactions to gameplay

No, no we shouldn’t. It’s hard playing a VR game for the first time especially with people you don’t know. We design The Room to be played at the players pace, lost inside an interactive world they enjoy. When people know you are watching they don’t play in their natural state or pace and they make more mistakes.

Solution: Leave players alone; ask them the annoying questions once finished.

2) The Room is already so tactile on mobile, we’ll ace the feeling of interaction in VR

Ah ha ha ha. Fools. With Room Mobile games we could fill small spaces with detail knowing the camera will see it. In VR, the player can look anywhere at any time and they prefer to look around than focus on every surface. Secondly touchscreens are exact one-to-one feedback interfaces. By contrast, placing a hand in VR space is about modelling a feel and consistency to the controls in three dimensions. Above all, we didn’t want the players’ hands to flap uselessly about or the objects they play with to feel weightless.

Solution: We had to put a lot of effort into modelling weight and resistances and adjusting the controls to make the players hand movements feel direct, physical, and impactful.

3) Getting stuck is bad, no wait, getting stuck is good

Puzzle games are strange beasts because human minds are strange things. Different brains interpret our puzzles differently, especially in VR, so if we estimate someone takes too long to figure a puzzle out the temptation is there to simplify, to smooth it out. This can be a Very. Bad. Call. The thing is, people like bumps. They enjoy figuring stuff out. Getting stuck and then unsticking yourself is the satisfaction players crave in the puzzles.

Solution: Is thinking ever a waste of time for a brain? Leave some hard problems hard to add some grit. Done right, the toughest challenges give the highest payoff.

4) The camera is the best part of a VR game to play… and the worst part to make

This was a doozie. Making mobile games we used to be able to take control of the camera away from the player to guide it to all the pretty things they needed to see in the world. Move that camera all you want, Mobile didn’t care. In contrast to this if you even think of grabbing the camera from the player VR will shoot the tires out of your car. This is because with VR the player’s head is the camera, and really, tossing the player’s head around VR space is bad form, especially if they have an aversion to vomit. Coupled with the fact that our players had to see every reaction to their actions on-screen, we radically changed how we approached visualizing puzzles and the narrative sequences between them.

Solution: Make sparkly things! In other words, we did a lot of work on leading the players’ eye, making them want to look in a certain direction so they knew what was going on at all times.

These are just a few of the many, many non-obvious things we’ve been taught by working in VR. At the time we made our mistakes we thought our problems were unique but now we see they’re the same many developers go through. Believe it or not there’s a comfort in that — it meant we didn’t go too off the rails, didn’t ask too much from the software, we just had naïve expectations for how hard and counter-intuitive some aspects would be.

Now that the game is done, all we can hope is that our efforts to make The Room VR: A Dark Matter super-playable were worth it and our learnings are there on the screen for all our players to see. If you do pick up a copy, you will let us know, won’t you?