I wish I could share my fellow PC Gamer writer Joshua Wolens’ optimism—in a piece he wrote earlier this week, Josh laid out a very clear example of how pushback from the people who actually create stuff can build safeguards around AI, using the recent Hollywood writer’s strike as an example. I think he’s right, but these things are often an uphill struggle.

Our copyright laws are scrambling to catch up, creative workers are—as Josh points out—having to plug in hours of difficult, potentially career-threatening work just to protect their livelihoods, and our governments are filled with people old enough to remember cassette tapes, now forced to reckon with a technology with implications we still don’t understand.

I’m not here to get all Luddite on you about AI—I think it’s dangerous, but there are genuinely applicable uses for deep learning algorithms. Instead, I’m here to talk about the existential dread of trying to critique AI-generated work, and how 2023’s increased rise in AI is hurting criticism itself.

This ‘has’ to be AI generated

(Image credit: Genvid)

The phrase “this has to be AI generated” is getting thrown around a lot this year. Recently, the experimental interactive Twitch-like thing Silent Hill: Ascension came under fire for its weird script.

In one of its many strange scenes, a ‘cameo’ character came stumbling out of the brush to talk about jams at gunpoint. The Silent Hill Jam Man‘s rambling was suspected to be a product of AI scripting right out the gate, ending the conversation with a lot of pointing and laughing. I pointed and laughed too: Jam Man was funny.

Old: “It’s bread”New: “I like to make jams” pic.twitter.com/GzVTdKrqIzNovember 25, 2023

But there are a dozen ways that a poorly-handed production can worsen a script, causing this kind of thing to happen before a single AI prompt gets involved. I worry that the “this has to be AI generated” warcry might become our weapon of choice going forward. When in reality—things can just be bad, sometimes.

Scepticism is warranted in the age of AI, and it’s a reasonable response to an internet flooded with algorithmic doppelgangers—but I think it’s a real problem for a couple of reasons.

AI has no intent

(Image credit: Unity)

Part of what makes games interesting—and what makes critiquing them fun—is that they’re usually built to achieve a certain impact. A horror game is trying to be scary, an FPS game is trying to feel snappy and responsive. Even if a game is trying to be hostile to the player for artistic reasons (or rejecting genre trends) it’s usually for a purpose.

When a game falls just short of its promises—like Starfield seems to have done—it can be compared to other games in its genre to figure out how that happened. You hear “Starfield feels outdated” a lot, and because we all have a decent idea of what a good roleplaying game tries to do, we can articulate why. Dissection is fascinating and fun in equal measure. We compare intent to the final work and reach a conclusion that teaches us something.

Intelligence is a misnomer, because an AI isn’t actually thinking about anything.

But AI-generated work can’t be looked at like this because it doesn’t have intent. There’s no mystery to how an AI generated a beautiful night sky unless you’re unfamiliar with the tech—it was trained on a dataset of thousands of other night skies, then it made an educated guess.

Intelligence is a misnomer, because an AI isn’t actually thinking about anything. The scripts, pieces of art, and code within a dataset have intentions, sure, but those intentions are diluted. If you have a thousand people talking all at once about different things, it just becomes white noise.

(Image credit: Disney / Marvel Studios)

While the person prompting the AI does technically hold some intent, it’s not comparable. The framing of a photograph, the pacing of a script, the chord progression of a piece of music: the prompter is considering none of it, boiling it down to instructions like “in the style of X” anyway. You can’t critique a prompter’s prompt in any meaningful way.

When you criticise something that’s been AI-generated, you spend more time trying to prove it’s generated rather than dissecting why it doesn’t work. AI turns good-faith critique into a really annoying Turing Test. We’re all just squinting at a picture with weird hands so we can have the satisfaction of saying ‘ah-ha! I knew this was a robot!’

Death of the robot

(Image credit: Bethesda)

Maybe the best way to cope with an AI-littered landscape is to go full “death of the author” on these robots. Unfortunately for the both of us, that means the words of a 1960s French philosopher have an impact on how we talk about videogames. I’m as upset about it as you are.

Outlined in Roland Barthes’ 1967 essay of the same name, the death of the author is a way of critiquing something by ignoring its creator’s intent and focusing on your response to the text itself as a kind of rebellion against authorial voice. It’s by no means gospel, but let’s take the idea and run with it. If an AI can’t make something with intent, then you just apply Barthes’ framework to it. Problem solved, right? Except we run into a different issue: AI doesn’t have intention, but it definitely inherits bias.

It’s a common misconception that AI algorithms are somehow objective, devoid of all those pesky little things we absorb as we grow up in a society. In truth, AI is just a mirror of the datasets it’s trained on. There are plenty of examples of internet trolls hotwiring language models to say something horrific or AI art programs whitewashing people of colour.

The companies developing these programs know this, too. An investigation by Time into ChatGPT just this year discovered that the company was sending “thousands of snippets to an outsourcing firm in Kenya” to make sure it didn’t produce harmful content—at the expense of those forced to trawl through it.

(Image credit: MirageC / Getty/ OpenAI)

Critiques that ignore the problems of their authors can be interesting and illuminating, but only alongside knowledge of the author itself. If there’s no author to discuss, then there’s no author to ignore.

Barthes himself frames the death of the author as a kind of rebellion that allows the reader to create something new, their interpretation a novel text in itself: “Succeeding the Author, the scriptor no longer bears within him passions, humours, feelings, impressions, but rather this immense dictionary from which he draws a writing that can know no halt.”

I want to be able to meaningfully discuss games. Even bad ones.

The author dies, they don’t disappear. Dead men tell no tales, but dead people still have obituaries. You still know about them, you still learn about them, and ignoring whatever ideas they might’ve had can be educating, fun, and significant.

But if there’s no author to succeed, if Barthes’ death of the author isn’t a choice to be made when interpreting a text (but a requirement to engage with it at all) does the framework have any meaning? What does the interpretation then get used for, another prompt? More fuel for a dataset? I don’t know, but thinking about it gives me vertigo.

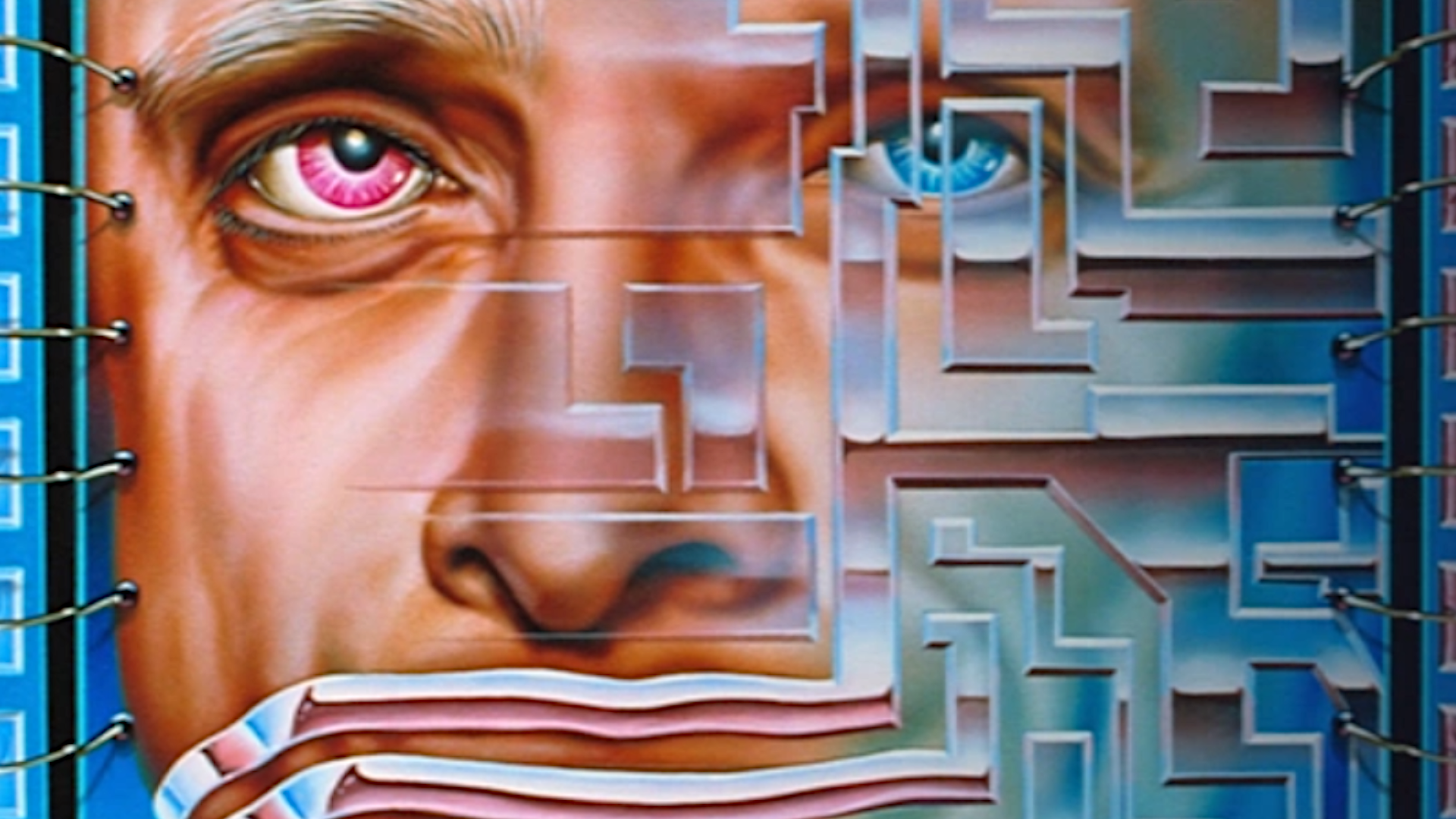

(Image credit: Stable Diffusion / Greg Rutowski / Creative Bloq)

We can draw circles around pieces of janky art or laugh at bizarre scripts all we want, but I genuinely think if you want to say something meaningful about AI-generated art, you’re just going to come up feeling… empty. AI doesn’t have intent, so you can’t critique it based on that. But it doesn’t have an author to rebel against, so interpretation-based criticism loses its spice and purpose.

An AI-generated future is one where we lose the words to talk about the things we love. How to make art or music or games—good and bad. I’m being very doom and gloom here, and there’s no guarantee things will get that dystopian, but I want to be able to meaningfully discuss games. Even bad ones. Even Jam Man.