What is it? A sprawling science-fantasy RPG

Expect to pay: $30/£25

Developer: Freehold Games

Publisher: Kitfox Games

Reviewed on: Radeon RX 6800 XT, Ryzen 9 5900, 32GB RAM (but it runs on a potato)

Multiplayer? No

Link: Official website

Across the great salt desert there is a jungled plateau encircled by mountains and speckled with the ruins of an advanced, ancient civilization. At its center lies the Spindle, a towering cable that stretches into and through the heavens. This is where your stranger arrives, the protagonist in an epic science-fantasy RPG full of engrossing stories and elegantly-designed, deep world simulation. It’s the best one I’ve ever played.

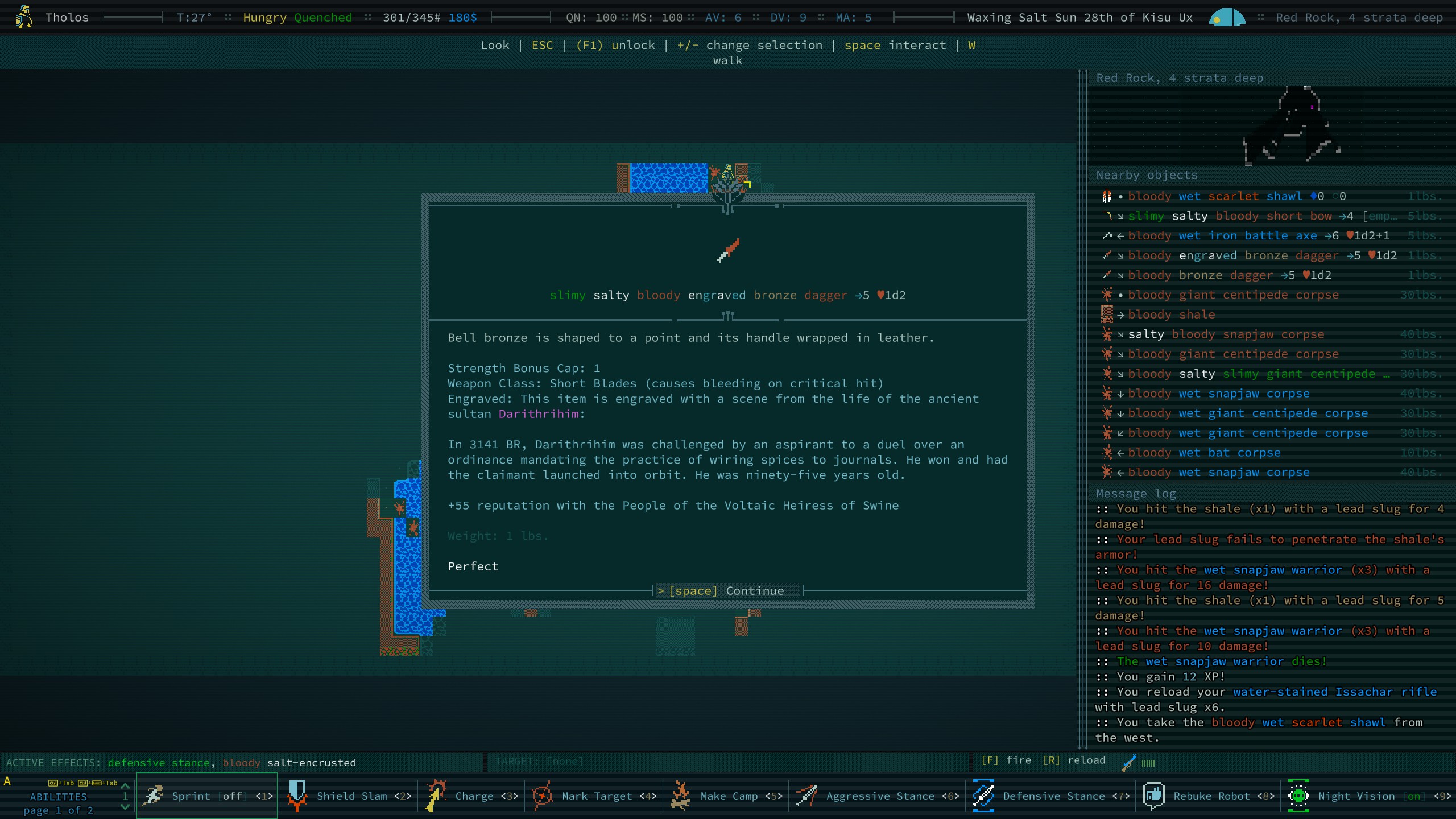

Caves of Qud is a traditional roguelike RPG in form, a top-down, turn-based game that relies on text and simple-yet-evocative graphics to convey its world. It doesn’t stick hard and fast to permanent death, though, instead letting you choose whether you want save points and even tweak how much fighting you’ll have to do. Nor does Qud stick hard and fast to the traditional roguelike rules of having an opaque, frustrating user interface and arcane, entirely keyboard-driven control scheme—it even plays very well on a mobile PC like the Steam Deck.

You make your character from a variety of archetypes that describe normal humans or the far more numerous mutant inhabitants of Qud. You then build in a relatively freeform way, choosing new skills, upgrading your abilities, and gathering equipment for a dizzying and thrilling array of possibilities. From there you set off across Qud from your starting village in true RPG sandbox fashion, choosing to follow or not follow the many quests and whimsical distractions you may come across. A lot of that will involve carefully delving into the ruins of the ancient civilization of the Eaters of Earth, fighting the strange and deadly creatures you find there, and pilfering their treasures.

Each playthrough has the same world map but randomizes nearly every local area according to a complex system of generated histories chronicling the sultans who ruled Qud in ages past. What they did then influences what you find now, where you go, and what you can expect to find there—and it integrates that generated history into the main story quest’s fixed objectives in clever and subtle ways that you might otherwise think had the hand of a designer behind them. Though it may take you a hundred hours to really get to grips with and master Qud, a seasoned player can burn through the main story in 15 hours.

Layer qake

The big-idea, high weirdness science-fantasy world of Qud’s far future is of an old genre (think Dune) with its own tropes, such as influence from ancient mideast cultures and mythology, but one that’s so underutilized in videogames that the setting comes off as refreshing. The spires of humanity’s utterly ruined past sit below and on top of Qud, forming a layer cake of dungeons filled with objects from a civilization so outrageously advanced that they invented teleportation and mined the neutron-degenerate matter at the heart of dead stars. The Eaters’ civilization was once so advanced that its fall was just as spectacular as its rise, leaving Qud a vast ruin cut off from the universe and scoured by terrible plagues—fresh water is so precious, for example, that a dram of water is the only true currency on Qud.

Pure-blooded “normal” people have become one of many different successor species and ancient genetic engineering combined with reality-altering phenomena have unleashed a tidal wave of strange creatures onto this world—the many talking plants, for example, barely register as exciting compared to a Twinning Lamprey, which exists in a strange quantum state where only when both its bodies are killed simultaneously will it die. Qud is a world where you start off fighting Hyena-people in a swamp with a bronze dagger and end it clad in zetachrome armor made of forgotten matter from the start of the universe, fighting mecha and cosmic terrors while wielding an eigenrifle that fires a subatomic particle beam capable of piercing through every single thing on the screen, friend or foe.

Rich storytelling

The main quest takes you on a journey well-suited to pit stops, dotted with odd characters like a deaf-mute albino bear-porcupine gunsmith and a very rude talking fungus you have to bring with you by letting it grow on your skin. It also stays varied: You’ll delve ancient ruins for lost technology, yes, but also manage diplomacy among factions, make friends, solve riddles, and unpick that generated history. All of this is written in a prose so flowery and rich that it passes beyond purple and arrives in the same place as something like Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, utterly unafraid to pillage the depths of the English language for the right words and then invent its own words when those don’t quite cut it. I could fill this review with phrases cut from item descriptions. (“It’s a large piece of rock, older than every idea” reads the description for a boulder. “Its shelled torso is downside up and sprouts a bouquet of crumpled legs,” I’m told about the corpse of a giant crab.)

The world and writing and story are so appealing in part because Qud draws from a diverse set of sources that aren’t just other videogames and obvious, obligate nerd pop culture stuff. Its cultural borders extend well outside the limits of so many games. It’s rare we get the pleasure of playing a videogame influenced by Dune or The Book of the New Sun or Gamma World that also freely quotes Lord Byron and A.E. Housman while drawing elaborate allusions to the Hebrew Bible.

Get weird

Qud’s world is powered by a physics simulation that lets you drill through walls with a jackhammer or melt rock into lava or spread clouds of corrosive gas that shift in the wind.

Your character’s traits and background will be just as rich as the world’s. You might play a True Kin, one of the last unmutated remnants of old humanity close enough to their biology and genome that the Eaters’ technology, robots, cybernetic implants, and miracle medicines still recognize and work for you, enhancing yourself with cyberware like extra-large hands and firearm hardpoints to wield four two-handed chainguns at once. You might instead be a mutant with a beak, wings, night vision, and talons whose mutations grow in power so that they can sunder steel. Your mutant might have psychic powers like cryokinesis and telepathy and disintegration. You might even play as a purely physical chimera that grows twelve arms, or a purely psychic esper who becomes so powerful that their Glimmer attracts extradimensional hunters and predators from beyond our own universe.

It’s not just variety that makes Qud so fun, it’s the depth of simulation in the world you explore. Aside from your health value or the rare damage calculation that can go to the hundreds, you rarely have to deal with numbers larger than 30 when considering statistics and attributes. But Qud’s world is powered by a physics simulation that lets you drill through walls with a jackhammer or melt rock into lava or spread clouds of corrosive gas that shift in the wind. The characters you meet all have a faction and a base attitude and an allegiance to it that plays out in hilarious ways: You might be beloved by apes, causing the shaggy white monsters that roam the canyons to leap to your defense, or hated by insects, causing typically chill giant dragonflies to come after you with a vengeance. Manipulating other factions’ attitudes toward you is key to enjoying Qud, causing you to form alliances with groups like the machine-worshipping Mechanimists or become self-appointed protector of the villagers of a randomly generated town. I defended one with my life because I thought it was hilarious that its mayor was a talking pig that was hated by other swine for “defiling their holy places.”

Stay weird

Random generation can of course make or break a game like Qud. Sometimes it’s against you in the most hilarious ways, sometimes it’s just frustrating as you plumb some deep stratum praying that the next chest has some upgrade—please, any upgrade—for your gun or armor. Sometimes it’s for you as it spits out a unique relic that feels purpose-made to fit just the character you wanted to play—as a sword-wielding knight I once found a shield that could reflect enemy lasers back at them.

Your tolerance for unpleasant, run-ending (or save-reloading) surprises has to be pretty high as you first discover things like which robot is armed with missile racks and how to kill a Twinning Lamprey and how when you see a biblically accurate angel you should just run away. You can contract infections or lose a limb, but to enjoy yourself those must be interesting problems to solve or situations to exploit, part of your overall story rather than frustrations. The fun to find in Qud is about learning—reading the flavor text for hints, figuring out which randomly-generated named creature to befriend, and carrying a variety of tools for different situations. Always have an EMP grenade on hand, for example, to deal with wayward robots. You have to be willing to try and fail and to learn when it’s better to run away, consolidate your gains, and try again tomorrow. Every challenge in Qud was not hand-made to be beaten. Quite the opposite, in fact.

That is no surprise to fans of the traditional roguelike’s deep details and convoluted systems and surprising random events. For others it will be unpleasant at first. Caves of Qud has what is likely the best, most modern interface and controls in a game of its kind, but the experience is still at times frustrating as you try to unravel just what happened in the last combat round that caused you to die. For some who have not played games like this before, simply the act of learning to control and maneuver your character will be frustrating. Despite this I cannot recommend Caves of Qud enough for its innovations in mechanics and storytelling, however anachronistic it may look.

Besides, on top of it all? You can easily mod this game.