When the RTX Blackwell GPUs were first announced during CEO Jen-Hsun Huang’s CES 2025 keynote, the big news was around the fact the RTX 5070 could deliver the same level of gaming performance as the RTX 4090. That was a new $549 GPU delivering frame rates akin to a $1,600 card of the previous generation.

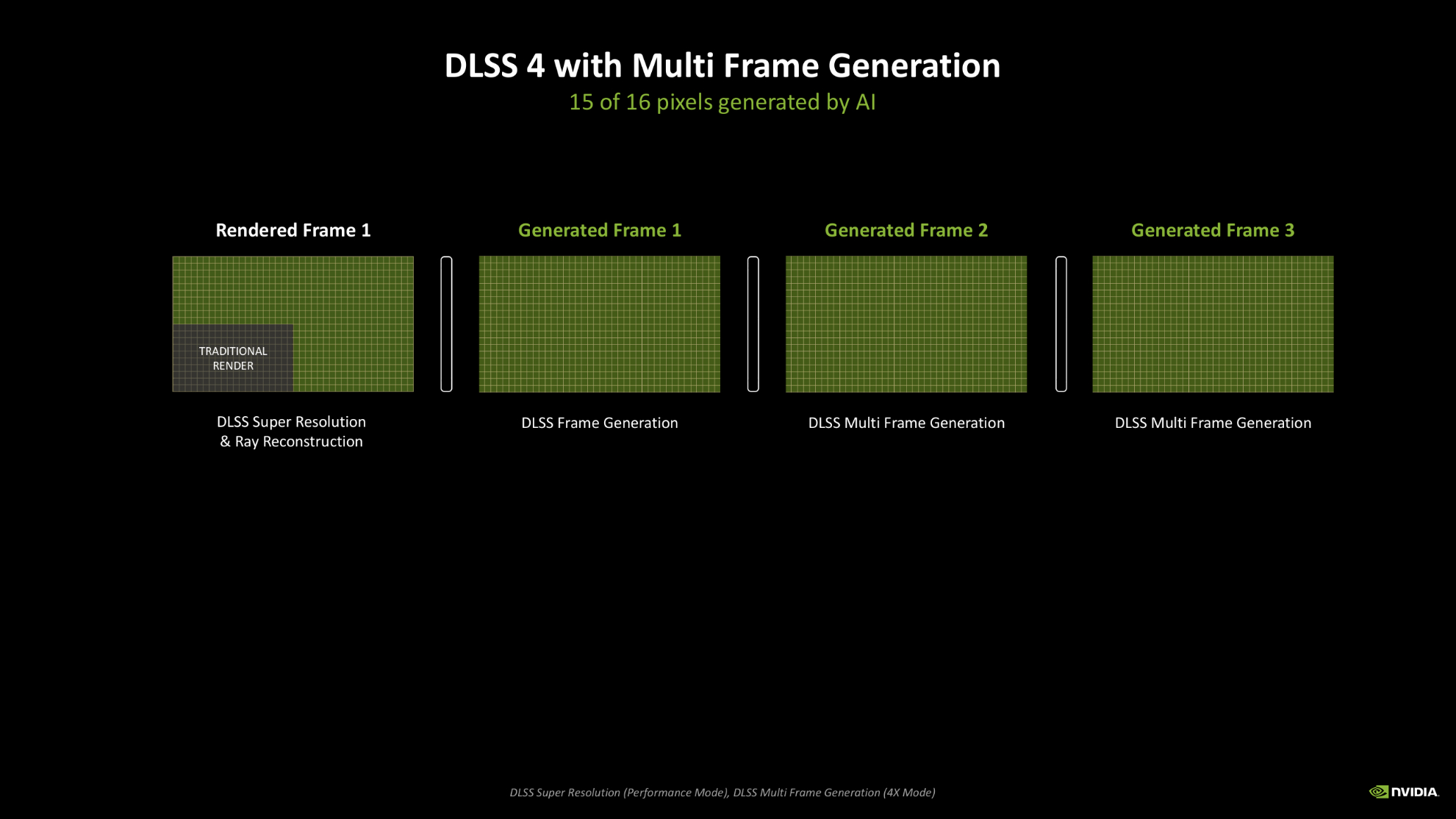

Then it became clear that such performance claims came with the heavy caveat that you needed to enable DLSS 4 and Multi Frame Generation to deliver the same frame rates as an RTX 4090 and suddenly the question of generation-on-generation performance became a hot topic.

Now the Nvidia RTX Blackwell Editor’s Day embargo is up we’re allowed to talk about the gen-on-gen performance numbers the company provided during a talk on the new RTX 50-series cards by Justin Walker, Nvidia’s senior director of product management. And if you held any illusions the silicon-based performance jump might be in some way similar to what we saw shifting from Ampere to Ada, I’m afraid I’m probably about to disappoint you.

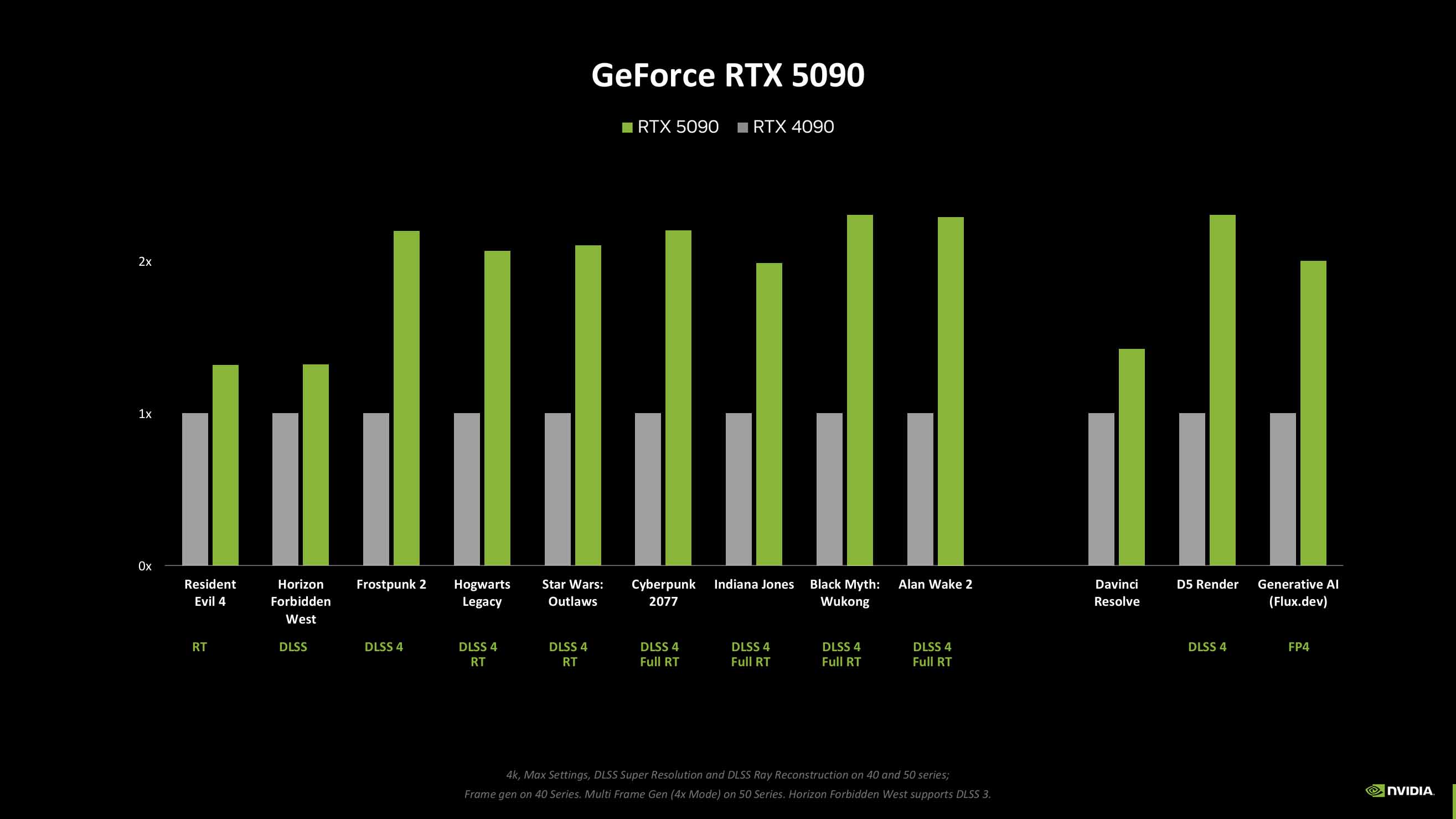

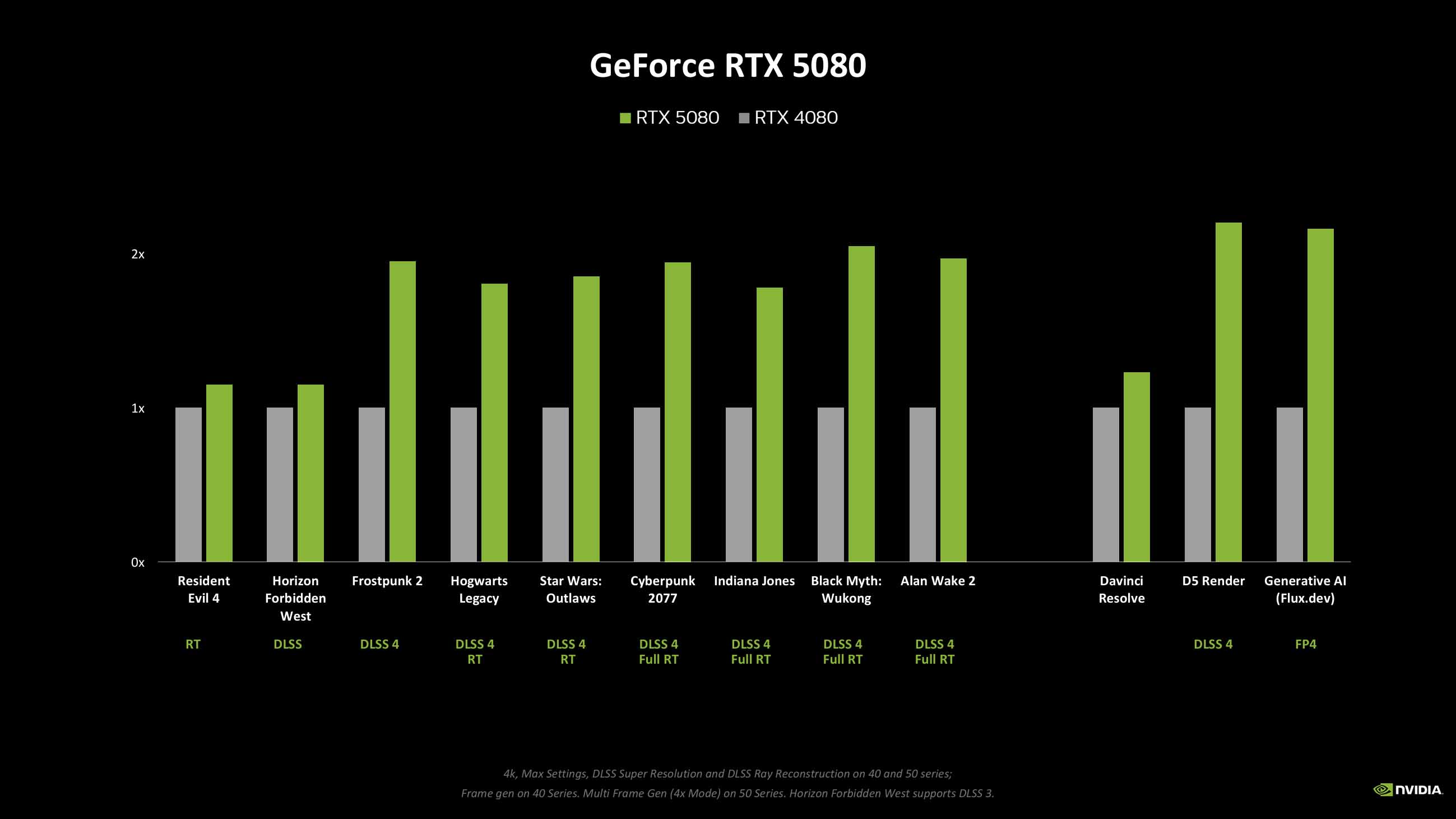

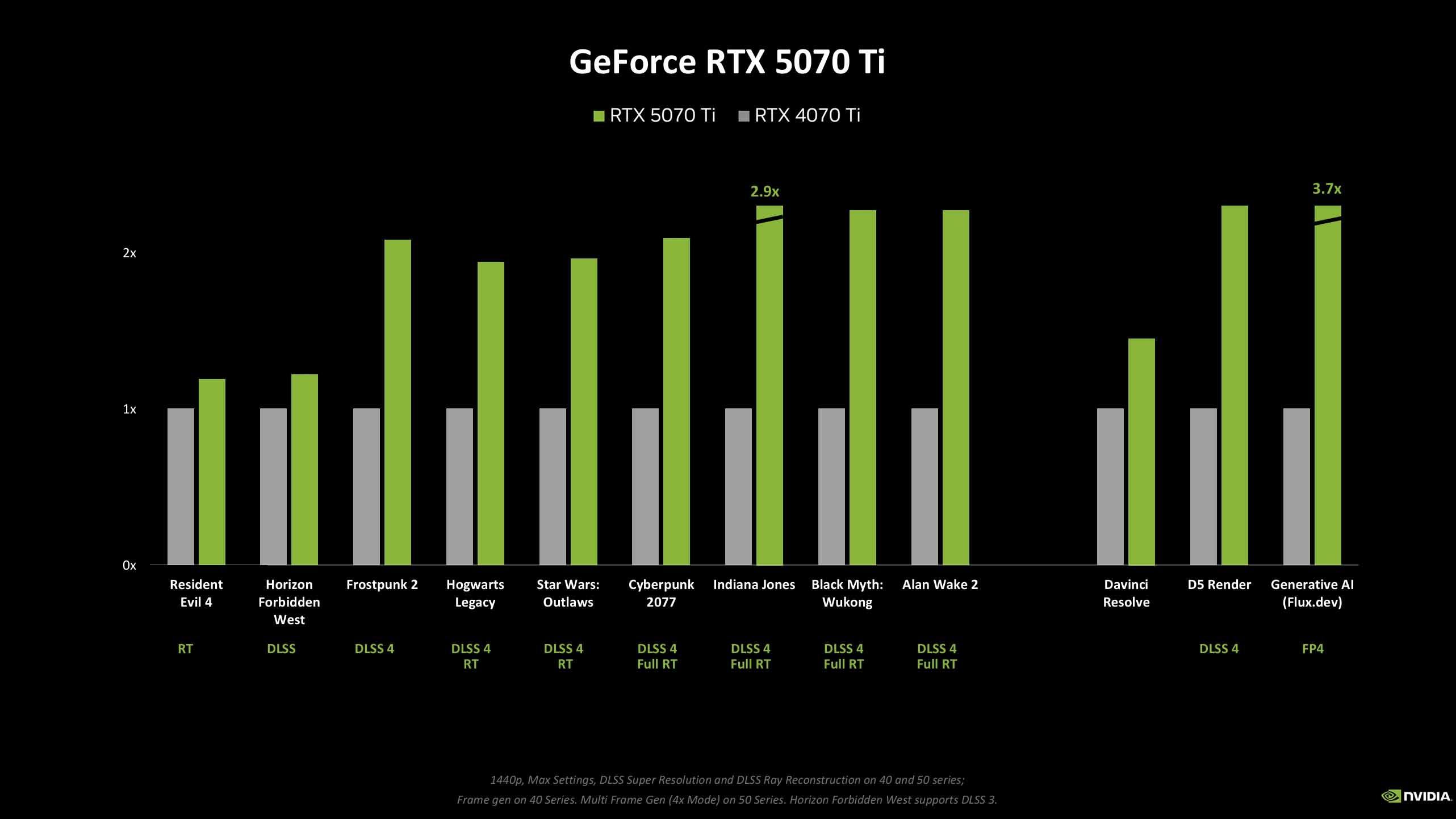

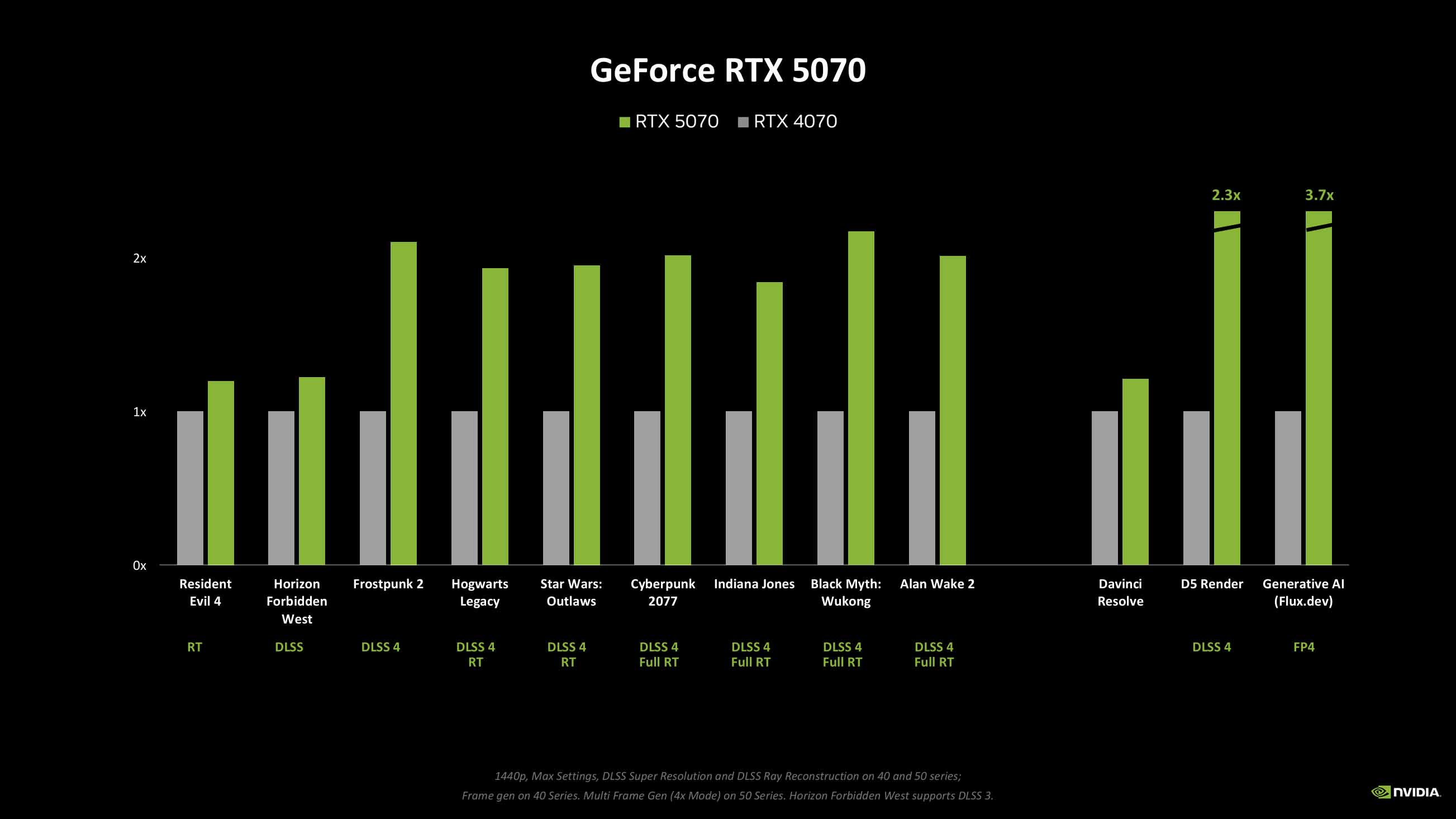

You can see in the slides below just where the four different RTX Blackwell GPUs stack up, both in terms of straight gen-on-gen performance, as well how they look when you include the multi-gen AI might of DLSS 4 and Multi Frame Generation.

As expected, the RTX 5090, with its healthy dollop of extra TSMC 4N CUDA cores is the winner out of all the new cards. You’re looking at a straight ~30% performance uplift over the RTX 4090 when you take Frame Gen out of the equation, and a doubling of performance when you do.

Either way, it’s a genuine performance boost over the previous generation. Though, it must be said it’s considerably more expensive, and doesn’t come close to the performance uplift we saw from the RTX 3090 to the RTX 4090. I’ve just retested both in our updated graphics card test suite, with the mighty AMD Ryzen 7 9800X3D at its heart, and the Ada card was delivering around an 80% gen-on-gen uplift without touching on DLSS or Frame Gen.

The weakest of the four is the RTX 5080. Sure, its $999 price tag is lower than the $1,200 of the RTX 4080, and matches the RTX 4080 Super, but you’re looking at just a ~15% gen-on-gen frame rate boost over the RTX 4080. Going from the RTX 3080 to the RTX 4080 represented a near 60% frame rate bump at 4K, for reference. Even with Multi Frame Generation enabled the RTX 5080 isn’t always hitting the previously posited performance doubling.

Then we come to the RTX 5070 cards and their own ~20% performance bumps. And, you know, I’m kinda okay with that, especially for the $549 RTX 5070. I’d argue that in the mid-range the benefits of MFG are going to be more apparent, and feel more significant. Sure, that 12 GB VRAM number is going to bug people, but with the new Frame Gen model demanding some 30% less memory to do its job, that’s going to help. And then the new DLSS 4 transformer model boosts image quality, so you could potentially drop down a DLSS tier, too, and still get the same level of fidelity.

So, why aren’t we getting the same level of performance boost we saw from the shift from the RTX 30-series to the RTX 40-series? For one thing, the RTX 40-series was almost universally more expensive compared to the cards they replaced, and that’s not a sustainable model for anyone, not even a trillion dollar company.

Basically, silicon’s expensive, especially when you want to deliver serious performance gains using the same production node and essentially the same transistors. The phrase I kept hearing from Nvidia folk over the past week has been, ‘you know Moore’s Law is dead, right?’ And they’re not talking about some chipmunk-faced YouTuber, either.

The original economic ‘law’ first proposed by Intel’s Gordon Moore stated that the reducing cost of transistors would lead to the doubling of transistor density in integrated circuits every year, which was then revised down to every two years. But it no longer really works that way, as the cost of transistors in advanced nodes has increased to counter such positive progression.

That means, even if it were physically viable, it’s financially prohibitive to jam a ton more transistors into your next-gen GPU and still maintain a price point that doesn’t make your customers want to sick up in their mouths. And neither Nvidia nor AMD want to cut their margins or average selling prices in the face of investors who care not a whit for hitting 240 fps in your favourite games.

So, what do you do? You find other ways to boost performance. You lean on your decades of work in the AI space and leverage that to find ways to squeeze more frames per second out of essentially the same silicon. That’s what Nvidia has done here, and it’s hard to argue against it. We’d have all been grabbing the pitchforks had it not pulled the AI levers and simply built bigger, far more costly GPUs, and charged us the earth for the privilege of maybe another 20% higher frame rates on top of what we already have.

Instead, whatever your feelings on ‘fake frames’ are, we can now use AI to generate 15 out of every 16 pixels when we’re rocking DLSS 4 and Multi Frame Generation and find ourselves with a $549 graphics card that can give us triple figure frame rates at 1440p in all the latest games. When you’re getting a seamless, smooth, artifact-free gaming experience, how much are you worried about which pixel is generated and which is rendered?

Maybe I sound like an Nvidia apologist right now, and maybe the bottomless coffee at the Editor’s Day was actually the koolaid, but I see the problem. Hardware is hard, and we have a new AI way to tackle the problem, so why not use it? A significant process node shrink, down to 2N or the like, could help in the next generation, but until we get functional, consumer-level chiplet GPUs another huge leap in raw silicon performance is too costly to be likely any time soon.

So, once more, I find myself bowing down to our new AI overlords.