There’s a decent chance that any given website you visit runs on WordPress. Businesses large and small, along with big-name media outlets, swear by it. According to an oft-cited estimate, more than 40% of the web uses the open-source content management platform, originally built for blogging, to do all kinds of things. At one time, PC Gamer’s website ran on WordPress.

But now there’s a problem: In the past six months, the project’s co-founder and longtime leader has alienated large chunks of its user and developer base, culminating in courtroom battles and repeated public spats. The reason, when boiled down? Competition.

Matt Mullenweg, who started the WordPress project in 2003 and still leads it, has long sold WordPress services through his company Automattic. The company also manages a host of side businesses—like the social network Tumblr, the podcast app Pocket Casts, and the messaging app Beeper—but WordPress is Automattic’s baby, and Mullenweg is very protective of it.

Mullenweg has been called a “benevolent dictator for life,” a humorous term used to describe open-source project leaders who shape a project’s long-term vision. But the fact that he also makes money from it clearly complicates things, because WordPress helps a lot of other people make money—and sometimes, Mullenweg gets upset about it.

Recently, Mullenweg publicly called out WP Engine, a fellow WordPress hosting provider that focuses on large businesses and marketing agencies, accusing it of confusing branding and exploitative practices. (“My own mother was confused and thought WP Engine was an official thing,” he wrote at one point.)

WP Engine, upset by Mullenweg’s public outbursts, sued—and late last year, it won a preliminary injunction against Mullenweg and Automattic in a federal lawsuit.

Mullenweg’s actions against WP Engine have had the drip-drip of a soap opera, while leaving lots of individual users in the middle—some of whom are stuck maintaining complex sites on a platform laden with tension and drama.

Here’s how things started, and where they stand today.

2003-2017: The Early Days

The WordPress project dates to 2003, after a 19-year-old Mullenweg, joined by Mike Little, decided to fork b2/cafelog, a precursor that had slowed down its development. Mullenweg saw an opportunity to modernize it, which led the fork to quickly usurp both its predecessor and dominate the blogging community at the time.

This proved the catalyst for the proliferation of businesses around the WordPress ecosystem. Many of these hosting providers were built around smaller-scale sites, however—the blogs WordPress was originally associated with. Large businesses were interested in WordPress, but early on, it wasn’t a fit.

That was the niche WP Engine was launched to fill. Dating to 2010, WP Engine offered “managed” WordPress hosting, meaning it handled the nitty-gritty server stuff for website owners—especially important when working with a large or highly valuable domain. Automattic, notably, invested in the venture in 2011, the first led by its A8c Ventures offshoot.

During the 2010s, WordPress was second only to Linux in prominence and name recognition in the open-source ecosystem—something both Automattic and WP Engine benefited from.

2018-2024: Tensions rise between WordPress and WP Engine

Over time, WP Engine’s business grew more prominent, and was often seen by corporations and marketing agencies as the preferred choice for hosting websites without a lot of frustration. While other companies, including Automattic’s own WordPress VIP offering, supported the ecosystem, WP Engine’s ease of management made it a favorite among high-value customers.

That led to a significant investment by the private equity firm Silver Lake in 2018.

And that investment, marked at $250 million, eventually became a major point of contention for Mullenweg. In Mullenweg’s view, WP Engine failed to invest some of its success back into WordPress. (Under most open-source licenses, there is no requirement to support the project, but for large companies, not pitching in is seen as poor form.)

Mullenweg’s frustrations reportedly simmered in behind-the-scenes negotiations—until one day last fall, when they exploded at a WordPress community event.

In his WordCamp US presentation, based on a blog post he published around the same time, he made clear he was ready to make waves. It literally carried the title, “WordPress Co-Founder Matt Mullenweg’s Spiciest WordCamp Talk Ever!“

Mullenweg’s beef leaned on WordPress’ trademark, which he said WP Engine used without contributing significantly to WordPress’ core, as well as changes that WP Engine made to its implementation that differed from the open-source project.

“Silver Lake doesn’t give a dang about your open-source ideals, it just wants return on capital,” Mullenweg said on the stage. “So it’s at this point that I ask everyone in the WordPress Community to go vote with your wallet.”

That was edgy enough, given that WP Engine sponsored the event. But in a cease-and-desist released days later, WP Engine and its law firm claimed Mullenweg had been using the event to shake down a licensing deal said to be in the tens of millions per year.

“When his outrageous financial demands were not met, Mr. Mullenweg carried out his threats by making repeated false claims disparaging WP Engine to its employees, its customers, and the world,” the document stated.

Mullenweg, for his part, says the action came after failed negotiations and concerns about WP Engine’s brand creating customer confusion.

“Finally, I drew a line in the sand, which they have now leapt over,” he wrote on his blog.

Fall 2024: Things get silly, then litigious

From that starting point, things got out of hand almost immediately, with users and open-source contributors caught in the middle. Mullenweg cut WP Engine’s access to WordPress.org—a repository similar to an app store for themes and plugins. In the process, he revealed that he personally owned the website, rather than the nonprofit WordPress Foundation.

He pressured WP Engine’s customers to leave the platform, while publicly claiming WP Engine launched a smear campaign against him. But many community members felt the opposite was happening.

Throughout October 2024, stories of longtime contributors getting banned from Slack channels or voluntarily quitting weren’t uncommon.

While tweeting and Slacking through it, Mullenweg supported his case in lengthy interviews with streamers ThePrimeagen and Theo Browne. Those appearances, as well as Mullenweg’s online interactions on various social platforms, became screenshot fodder for WP Engine’s legal case.

“Because WPE has effectively lost control of its ability to maintain its code on WordPress.org, users and customers of WPE will have outdated and/or potentially vulnerable WPE plugins,” the lawsuit stated.

Things weren’t any less messy internally at Automattic. Across multiple rounds of buyouts, nearly 10 percent of the company departed, with anonymous departing employees quoted in 404 Media raising questions about Mullenweg’s management style.

“He clearly has no clue what people care about or how the community has contributed to the success of WordPress,” one employee told the outlet. “It very clearly shows how out of touch he is with everyday reality.”

While many departing employees did not speak publicly for fear of retribution, a retired Automatic executive, Kellie Peterson, used her prominent voice to speak for concerned former employees.

“My main motivation right now is to help protect the WordPress community,” she said in a video targeted at departing employees.

Winter 2024: What the lawsuit hath wrought (so far)

Mullenweg responded to the lawsuit by launching increasingly vindictive attacks, including barring a popular plugin maintained by WP Engine, Advanced Custom Fields, from the WordPress.org directory on security grounds, and replacing it with an open-source fork, Secure Custom Fields. The company also barred WP Engine employees from signing into the WordPress community website, requiring users to check a box next to the statement, “I am not affiliated with WP Engine in any way, financially or otherwise.” (These actions showed that, despite outward appearances, Automattic’s business directly influences the WordPress open-source project.)

Most surprising of all: Automattic launched a tracker of departing WP Engine customers, with many going to its first-party WP Engine competitor Pressable, which offered a discount to WP Engine refugees.

These actions and others ultimately were cited in a preliminary injunction, granted in December, that restored WP Engine’s access to WordPress. Federal judge Araceli Martinez-Olguin centered the customer in her decision.

“Those who have relied on the WordPress’ stability, and the continuity of support from for-fee service providers who have built businesses around WordPress, should not have to suffer the uncertainty, losses, and increased costs of doing business attendant to the parties’ current dispute,” she wrote.

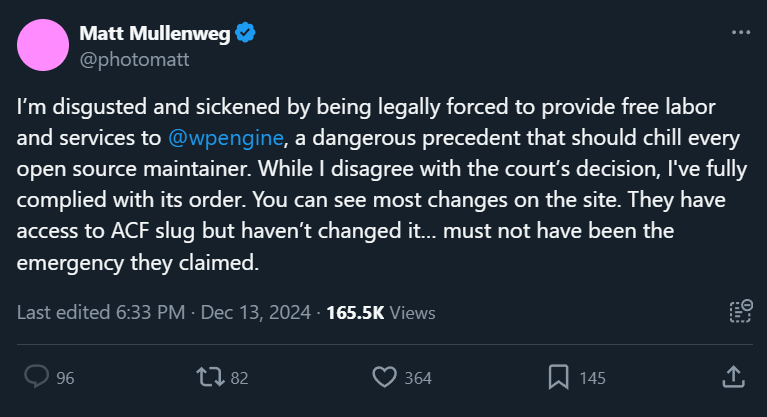

While Mullenweg clearly was not happy about it, he emphasized he would comply with the order.

“I’m disgusted and sickened by being legally forced to provide free labor and services to @wpengine, a dangerous precedent that should chill every open source maintainer,” he tweeted.

2025: Where things stand now

At this point, the effective outcome of the preliminary injunction is that the 41-year-old Mullenweg, for basically the first time in his adult life, is taking the pedal off the gas when it comes to WordPress. His company announced earlier this month that while it “remains deeply invested in the WordPress platform,” it would stop investing more than what’s absolutely required by a contributor covenant, slowing down Automattic’s open-source contributions from thousands of reported hours per week to the rough equivalent of one full-time employee.

For the first time in nearly 20 years, WordPress no longer feels like a sure bet if you need to get a website online.

“This legal action diverts significant time and energy that could otherwise be directed toward supporting WordPress’s growth and health,” the company wrote earlier this month.

The battle has taken a toll on Automattic’s valuation. Meanwhile, WP Engine and its users once again have access to the open-source project’s centralized theme and plugin libraries, but their future access to the platform is uncertain.

(The infamous checkbox remained, but amusingly, it now has people approvingly check the phrase “pineapple is delicious on pizza.”)

In the middle are all the people who host websites on WordPress—among them gaming enthusiasts, programmers, retailers, anyone you can imagine that hosts a website—who have been caught in the middle of a conflict between the company that manages their software and a company that primarily develops that software in the open-source ecosystem.

For the first time in nearly 20 years, WordPress no longer feels like a sure bet if you need to get a website online.