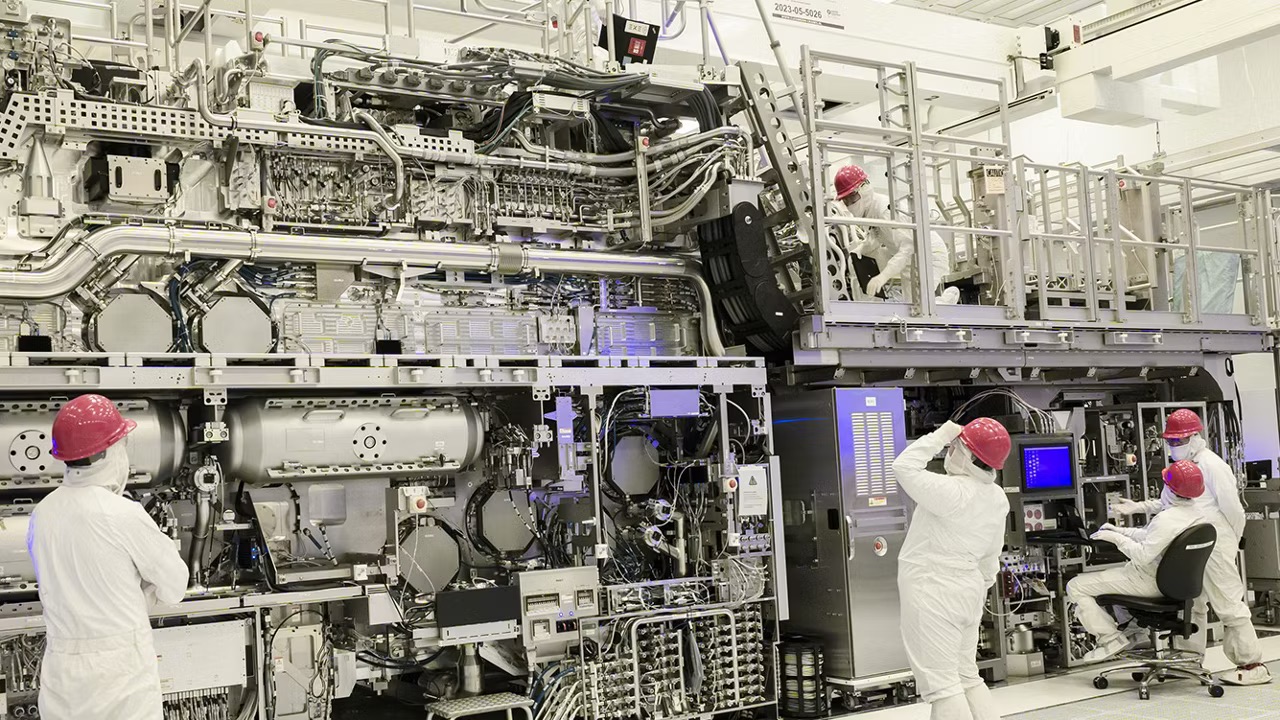

“Intel 18A is now ready.” So proclaims a new landing page on Intel’s website for the company’s all-important new 18A chip production node. But what does it mean for the PC?

We already knew that Intel’s next laptop chip, Panther Lake, is due to be made, at least in part, on the new 18A node. That’s supposed to be going into volume production later this year, though we’re not expecting 18A-powered laptops until early 2026.

Intel’s next desktop CPU, codenamed Nova Lake, is likewise a 2026 product according to Intel. So, what to make of Intel’s claims of immediate 18A readiness?

The new web portal is arguably more aimed at customers for its nascent foundry business than bigging up its own chips. “Intel 18A is now ready for customer projects with the tape outs beginning in the first half of 2025,” the website says.

In terms of in-house chips, Intel does call out the Clearwater Forest server CPU as an example of “18A in action” on the new website. Clearwater Forest was originally on Intel’s roadmaps as a 2025 product. However, at the end of January, Intel pushed Clearwater Forest back to the first half of 2026, which doesn’t exactly seem like a huge vote of confidence in 18A.

Of course, 18A is the final part of Intel’s bold “five nodes in four years” plan (also known as 5N4Y), which kicked off with Intel 7, then went to Intel 4 as used in the Meteor Lake mobile CPU, followed by Intel 3, Intel 20A and finally Intel 18A.

It was mid-2021 when Intel’s then-new-but-now-departed CEO Pat Gelsinger floated the idea. That means 18A needs to be ready for summer 2025 to be on track. With that in mind, the cynic might conclude that 18A’s announced readiness for customers, all the while Intel doesn’t seem to be able to get one of its own chips on 18A ready, is something of a PR stunt.

Arguably, you might conclude that about 5N4Y in general. Looking at each of the nodes in turn, Intel 7 is a version of the same 10nm technology that Intel had been struggling with for a decade, so not really a new node.

Intel 4 was certainly new, albeit a rebrand of the planned 7nm node. Calling Intel 3 a new node is a bit of a stretch, being as it is a revised on Intel 4. You could say the same about Intel 20A and 18A, but Intel cancelled 20A in any case.

So, at the very least, Intel is down to four nodes in four years. But taken in the round, of the five “new” nodes, only Intel 4 and Intel 18A are unambiguously new. And it remains to be seen whether any chips on 18A are actually available within Intel’s self-imposed time frame.

Still, if 18A is as good as Intel is cracking it up to be, whether it’s complete “ready” now or early next year probably doesn’t matter. It’ll be a great node that will not only enable some really competitive chips for Intel, but surely have customers queuing up to have their chips manufactured by the only real alternative to Taiwanese mega-foundry TSMC.

Among other advantages and refinements of the 18A node, Intel is making the following claims:

- Up to 15% better performance per watt and 30% better chip density vs. the Intel 3 process node.

- The earliest available sub-2nm advanced node manufactured in North America, offering a resilient supply alternative for customers.

- Industry-first PowerVia backside-power delivery technology, improving density and cell utilization by 5 to 10 percent and reducing resistive power delivery droop, resulting in up to 4 percent ISO-power performance improvement and greatly reduced inherent resistance (IR) drop vs. front-side power designs.

- RibbonFET gate-all-around (GAA) transistor technology, enabling precise control of electrical current. RibbonFET allows further miniaturization of chip components while reducing power leakage, a critical concern for increasingly-dense chips.

If 18A really does deliver on all that, it’ll certainly be highly competitive with anything TSMC has to offer. Broadly, Intel 18A is thought to be less dense in terms of logic gates than TSMC’s upcoming N2 node and more akin by that metric to the N3 node that TSMC has been banging out for about 18 months now.

However, another key measure is SRAM density. SRAM cells are used to provide critical on-chip cache memory. It was thought until recently that 18A was at best on par with TSMC N3 for SRAM density. However, it’s recently emerged that Intel 18A in fact offers pretty much exactly the same claimed SRAM density as TSMC N2.

Meanwhile, TSMC is not planning to include backside power delivery until its own A16 node. Long story short, backside power relocates the power interconnects from the top of the chip to the underside of the silicon layer, thereby separating it from signal interconnects. This reduces interference and shortens the distance power has to travel, which improves efficiency and performance.

As above, Intel 18A has backside power, which could be a big advantage over TSMC N2. Ultimately, we’ll have to wait and see. But we absolutely have our fingers and toes crossed that 18A works out. The alternative could be very bad for Intel. Gelsinger did say, after all, that he had “bet the whole company on 18A.”

And the way the chip industry is going these days, “very bad for Intel” could quickly turn into even more expensive chips for the PC.

We need as much competition in the industry as we can get. So, we generally agree with the sentiments an Intel engineer posted and then removed from Linkedin earlier this week, which basically boil down to not giving up on Intel just as it is about to turn things around with 18A.

Best CPU for gaming: Top chips from Intel and AMD.

Best gaming motherboard: The right boards.

Best graphics card: Your perfect pixel-pusher awaits.

Best SSD for gaming: Get into the game first.