There was once a world in which Rockstar published more than two games a decade. Difficult to believe, I know, but having lived through that halcyon period, I would testify to its existence in court.

A game like Manhunt 2 was sandwiched between Vice City Stories and Bully the year before, plus GTA 4 and Midnight Club: Los Angeles the year after. In fact, as a colourful demonstration of how busy Rockstar’s release schedule used to get, consider that the publisher was responsible for no fewer than four takes on Los Angeles over a span of eight years. That’s GTA 5, San Andreas, LA Noire and the aforementioned city racer, all open worlds.

It was a packed catalogue that allowed a subset of Rockstar games to be something they never are today: forgotten. Manhunt 2 now exists as a curio, more talked about than played. It’s most often remembered as a moment in which Rockstar’s controversy-baiting finally came home to roost—impacting not only marketing and perception, but the state the game actually launched in.

Rockstar’s history of courting bad press extends all the way back to the first Grand Theft Auto, which it promoted by hiring the notorious UK publicist Max Clifford—who later died in prison after being found guilty of eight indecent assaults on women and young girls. For GTA, Clifford planted stories and prodded at politicians, puppeteering the British political establishment until the game’s age rating was discussed in the House of Lords.

Without such cynical marketing, there’s a good chance GTA would never have ascended to become a global phenomenon. And so you can understand where the Manhunt series came from. A stealth concept about televised torture, in which players were rewarded with extra points for committing murder in the most explicitly awful fashion with plastic bags and garrottes, it had tabloid outrage baked into its DNA. Although that didn’t equate to blockbuster sales, Manhunt’s cult status only added to its video nasty appeal—which was enough to ensure it got greenlit for a sequel.

By that time, though, real trouble was bubbling up for Rockstar. Newspapers had blamed Manhunt for a teenage murder in the wake of the original game’s release, and with the help of anti-videogame activist Jack Thompson, calls to limit Manhunt 2’s sales emerged before its launch.

By the time Rockstar had appeased ratings boards, Manhunt 2 had been significantly censored.

“We are aware that in direct contradiction to all available evidence, certain individuals continue to link the original Manhunt title to the Warren Leblanc case in 2004,” Rockstar said in a statement at the time. “The transcript of the court case makes it quite clear what really happened. At sentencing the judge, defence, prosecution and Leicester police all emphasised that Manhunt played no part in the case.”

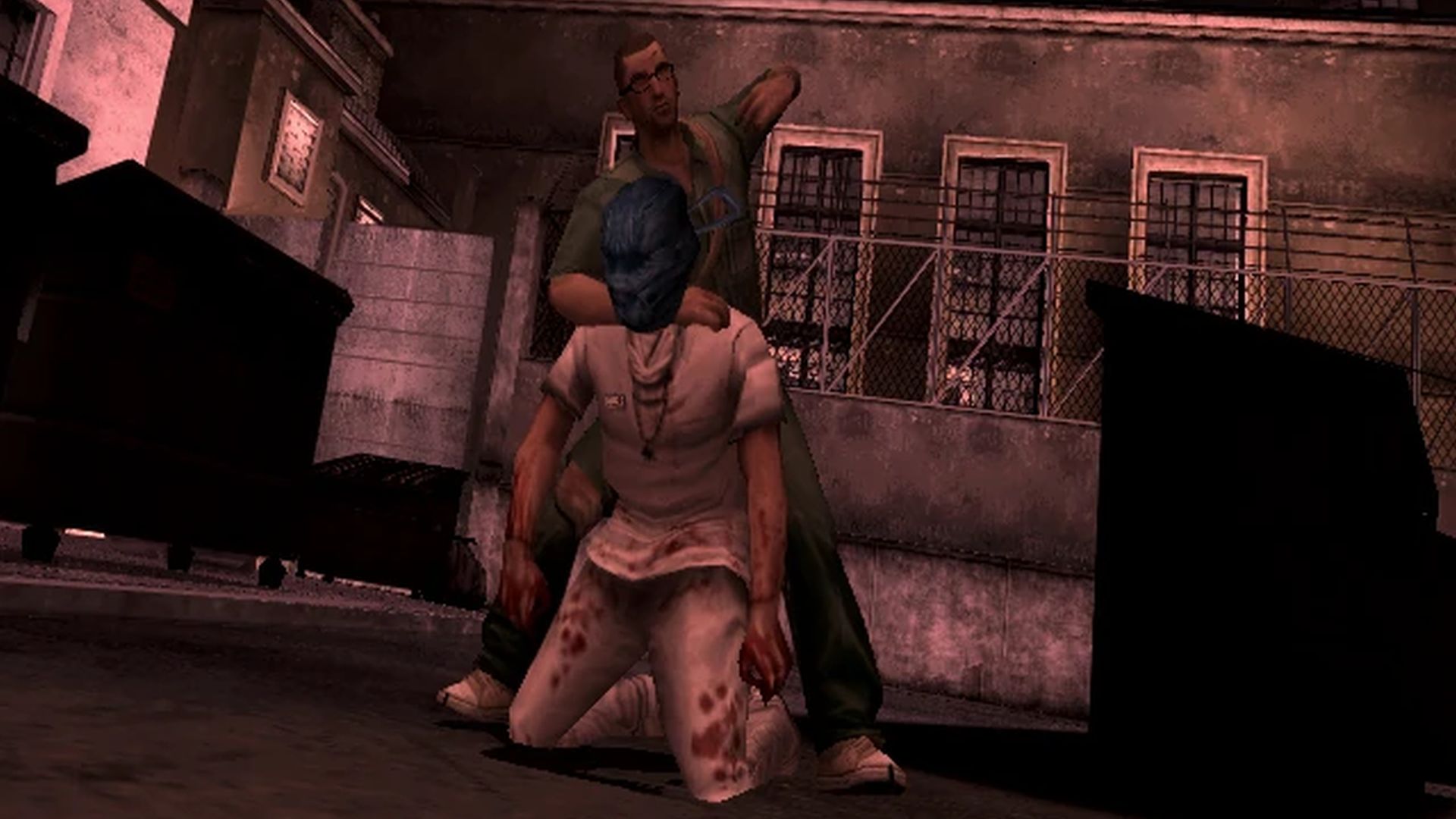

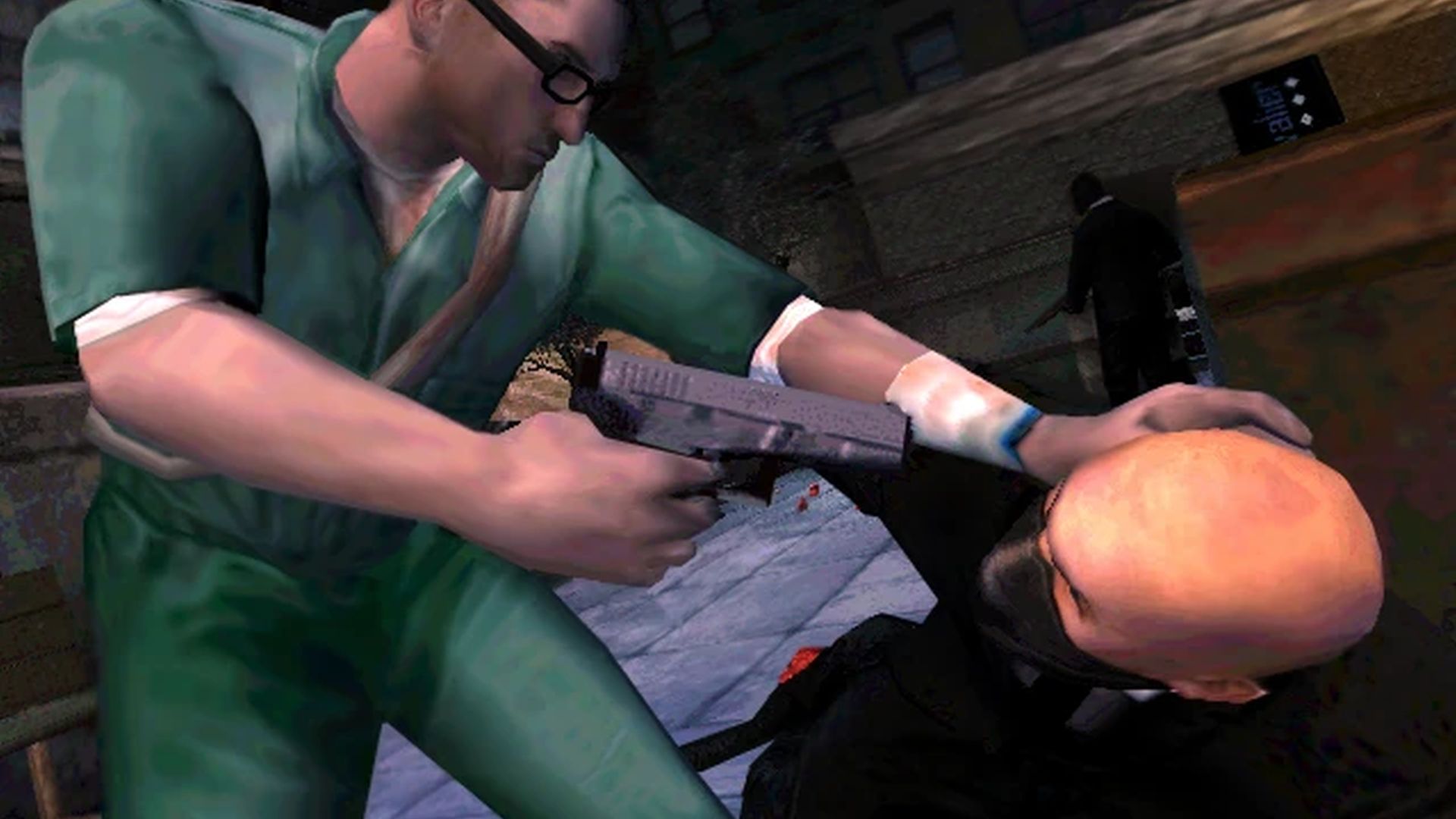

The publisher concluded that it would submit the game to the appropriate bodies, and expected to get an 18 rating. But that’s not exactly what happened. By the time Rockstar had appeased ratings boards, Manhunt 2 had been significantly censored. In particular, its killings were dramatically toned down, and blurred onscreen by a psychedelic cocktail of visual effects.

Oddly, this has left the difficult-to-find PC version of Manhunt 2 in a unique position. It’s the only place you can see the game’s takedown animations as they were first intended. Fans have covered the differences exhaustively on the Manhunt wiki, where you can find out precisely what happens to a man’s eyes when you attack him with a pair of pliers on your desktop.

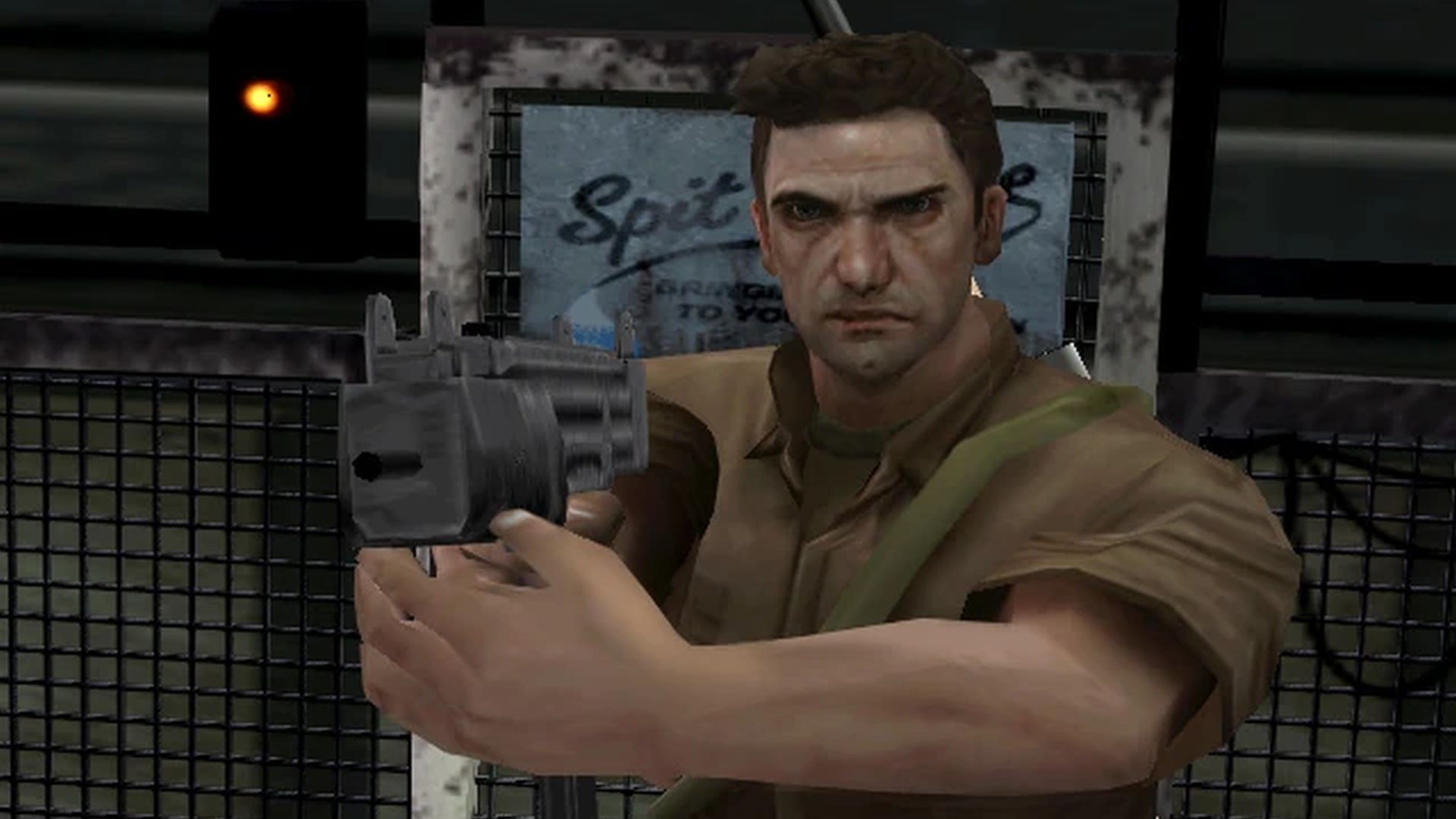

By contrast, I’ve been playing the PSP version on Vita—a remarkably full-featured port by the magicians at Chinatown Wars studio Rockstar Leeds. There, the attacks are noticeably blunted, in a very literal sense—jittery protagonist Danny Lamb treating every weapon as if it were an edgeless object, rather than taking advantage of the obvious properties of a massive pair of shears.

It’s as if Lamb was setting about his opponents with a big foam sword—or it would be, if they didn’t make the most terrible gurgling noises during the ordeal. Ratings boards tend to focus heavily on visuals, rather than sound, but as any horror aficionado will tell you, a scream or a snap is often much more evocative than fake blood. Audio has the capacity to stick with you long after the image has faded.

Discussion around Manhunt 2 online tends to focus on finding the definitive, uncut version, which I can understand. As someone perpetually on the side of the artists, I tend to seek out games and movies in the state their makers intended them. But in this case? I’m not sorry to be on the receiving end of a little censorship. I do not, in fact, need to see Danny plunge his hand into a victim’s neck and pull out their Adam’s apple. I prefer a Pink Lady or Granny Smith, and being able to sleep at night.

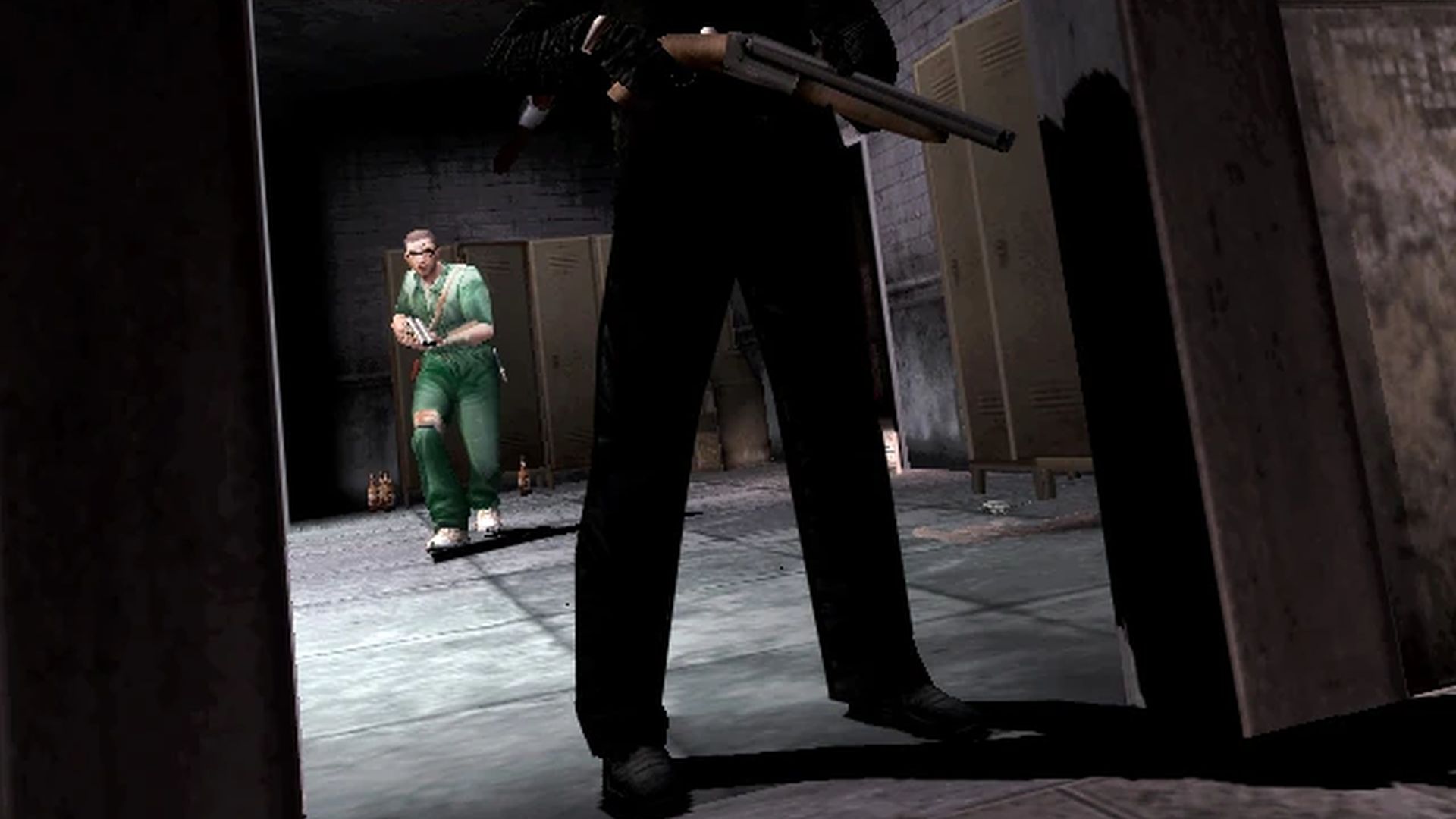

What bothers me more is the other consequence of the ratings hoo-ha: the lack of a score screen at the end of each level. A core mechanic of Manhunt—arguably its USP, the one thing that makes it stand out from its better-loved peer, Splinter Cell—is the ability to charge up takedowns before letting loose. The blows don’t get any more powerful, and bonking an unaware enemy on the head the moment their back is turned will remove them from the board just the same. But in the original game, you’d get a higher score for pulling off charged-up attacks, which treated your Squid Game audience of paying sickos to a grislier and more varied set of deaths. Not so in Manhunt 2.

“The scoring was a holdover from the first game, and when we had the opportunity to make edits because of the rating, we decided to remove it,” former Rockstar high-up Jeronimo Barrera told MTV in 2007. “We felt it flowed better without a score screen between levels.” Perhaps. But in what other game has a ratings board battle caused the entire metric by which player success is measured to be tossed out? Only on PC is there an incentive to creep slowly behind enemies as they move, holding down the attack key all the while. Otherwise, you’re merely doing it for your own professional pride, or disgusting gratification—delete as appropriate.

Improving the flow of Manhunt 2 might have been a sensible priority if it had a “really strong narrative”, as Barrera claimed. But despite flourishes of non-chronology, its dual-personality horror is ultimately predictable. For a serial killer, Lamb is oddly passive in his own story—failing to piece together hard truths in his past you’ll have long since cottoned onto.

The harder truth for Manhunt 2 is that controversy does not, in the playing, make a game more interesting or brave or special. In fact, this is a distinctly safe sequel—failing to move beyond the mechanical confines of its predecessor, or make bold decisions as a psychological thriller.

Today, the most rewarding and alluring thing about Manhunt 2 is that it was among the last of its kind—a dedicated stealth game made by a blockbuster studio, shortly before Splinter Cell shifted into action-hybrid territory and the industry followed suit. Shoved between Bully and Midnight Club in the release schedule, this was a cat-and-mouse simulator of light and sound that demanded you sit in the shadows and wait out your enemies—the likes of which we rarely get today. That’s how Manhunt 2 is best appreciated, rather than as a graveyard of censored images related to the misuse of gardening equipment.